This post is a small digression from the main thread – I will write here about a new method for recreating geometry of historical airplanes.

In

one of my previous posts I complained that it is hard to find any reliable drawings of the historical propeller blades from the middle of 20

th century. In particular, the geometry of various popular Hamilton Standard propellers from WWII era is unavailable. I have found in a discussion on one of the aviation forums that Hamilton Standard Company still keeps this data as their “business secret” – even their design from 1936!

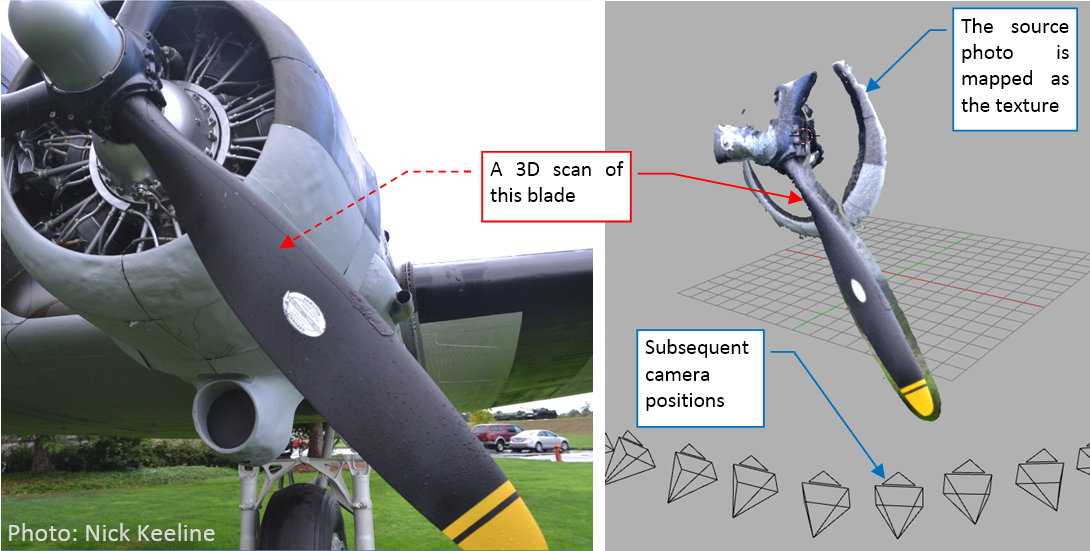

So far, all we had were the photos *– but it is really difficult to precisely recreate from a few pictures such a twisted, complex shape as the propeller blade. However, it seems that there is a new hope! Two years ago I encountered on Blender Artists forum an interesting project. The Author of this thread (nick: NRK) used one of the general photo-based 3D scanning methods to obtain a spatial reference of a C-47 aircraft. Although this is not the SBD Dauntless, it seems that its Hamilton Standard propeller blades are similar to the blades used in the earlier Dauntless versions (SBD-1 .. SBD-3). Thus I asked NRK for the part of his 3D scan that contains the propeller. He sent me it within a few weeks (thank you very much, Nick!). Below you can see the picture of this blade and the contents of the 3D scan:

Note for the C-47 buffs: it seems that this aircraft used two different types of the Hamilton Standard blades. Most of the C-47s used wide-blade propellers, similar to those from the B-17 bombers. However, it seems that some of the C-47s used older, thin-blade propellers, which you can see in the aircraft from the picture above. For example, I have found similar blades in another C-47 from Commemorative Air Force, which was built in 1944.

NRK’s 3D scan recreates only the upper (i.e. forward) propeller surface and its leading and trailing edge. However, it is still usable, because in most of the blades from this era their lower (i.e. rear) surface was flat. In this NACA report 642 (from 1937) I have found some tips about the airfoil used in the Hamilton Standard propellers: it could be R.A.F-6 or modified NACA-2400-34. Because the NACA-2400 had convex lower surface, I ultimately decided to use the R.A.F-6 airfoil:

R.A.F-6 is one of the pioneer airfoil shapes, designed in 1912. In that times engineers did most of the aircraft drawings with a chalk on the workshop floors. Thus the data points for this airfoil are relatively sparse, and leave some space for the handcraft – especially along the leading and trailing edges. I smoothed them using subdivision (i.e. B-spline) curves.

I connected this the R.A.F-6 airfoil to a circular base, creating in this way the initial segment of the propeller blade:

Then I fit this segment into the reference mesh:

As you can see on the picture above, the surface obtained from a 3D scan contains plenty of small irregularities. However, their presence helps to estimate the tolerance (i.e. the range of the shape deviations from the real surface) of this reference.

I formed the blade using the same methods as described in this post: by extruding and adjusting subsequent “ribs”. First I recreated the general contour in the front view:

I formed the tip using the same methods as in this post: first I put an auxiliary circle (as an additional reference), then I connected the leading and trailing edges around this shape:

Then I rotated this blade a little, placing the tip surface on the reference surface:

At this moment the tip is the only fragment of the blade that fits the scanned surface: all the other blade segments are below or above it, because they are not twisted (yet).

I will twist this blade using curve modifier (as I did in this post). Thus I created such a curve:

Initially it was a straight line, placed on the blade axis (as in figure "a:, above). Simultaneously it lies on the rear (flat) blade surface (Because I placed all of the blade sections above its axis *– see the third figure in this post).

The blade of such a shape is not balanced – the centrifugal force would tore it off from the propeller hub. To avoid this effect, all blade cross-sections should have their centers placed on the blade axis. Thus in the side view the blade should resemble a symmetric triangle. I sketched its contours in figure "c", above) using white dashed lines. To fit the lower (rear) blade surface to such a line, I deflected the deforming curve downward (rotating it around the tip – as in figure "b", above). However, to simultaneously fit the blade upper surface to the top contour, I had to alter the thickness of its airfoils (see figures "c" and "d", above).

Figure below shows the resulting, “balanced” blade (it is still not twisted):

Finally, I twisted this blade by twisting subsequent vertices of its deforming curve. I did it until the leading and trailing edge fit their counterparts on the reference surface:

It was the last step of this process. You can find the resulting Hamilton Standard propeller blade in this source *.blend file.

Although it is still based on some assumptions (for example – the airfoil shape), this is much better approximation of the real shape than my previous attempts.