Well, the time has come for me to make my first effort to post pictures in the Forum. I've bought a new computer (a Mac) and a new copy of Photoshop Elements 11, and I've set up a Photobucket account. Here goes nothing:

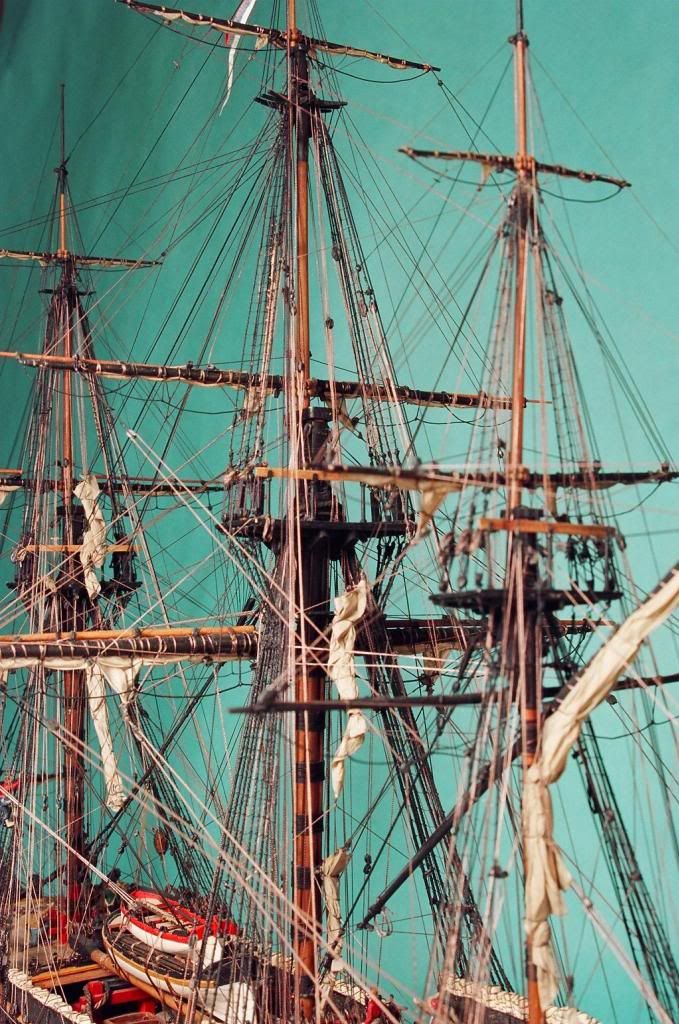

So far so good. I built this model of the American Continental Frigate Hancock between 1977 and 1983. The scale is 3/32"=1', or 1/128, giving it an overall length of about 20". It's scratchbuilt, with some manufactured parts (mainly the blocks, deadeyes, and crew figures). The construction method is "plank-on-hollowed-out-solid," with the hull carved from basswood lifts glued either side of a plywood "keel plate." The hull planking is strip styrene. I'm not sure I'd use that method again, but it worked. The glue that holds the planks to the hull has now been holding just fine for more than thirty years.

So far so good. I built this model of the American Continental Frigate Hancock between 1977 and 1983. The scale is 3/32"=1', or 1/128, giving it an overall length of about 20". It's scratchbuilt, with some manufactured parts (mainly the blocks, deadeyes, and crew figures). The construction method is "plank-on-hollowed-out-solid," with the hull carved from basswood lifts glued either side of a plywood "keel plate." The hull planking is strip styrene. I'm not sure I'd use that method again, but it worked. The glue that holds the planks to the hull has now been holding just fine for more than thirty years.

It's based on the drawings that the British made after they captured the ship - the "Admiralty draught." Howard I. Chapelle traced those drawings for publication in his great book, The History of the American Sailing Navy. I bought prints of the Chapelle drawings from the Smithsonian (where almost all of his drawings are held), took them to an architectural printing firm, and had them reduced from the original 1/48 to 1/128. In those days that reduction process was was rather complicated, requiring big, expensive equipment. Nowadays an architectural printer with a good xerox copier can do it in a few minutes - and if the original isn't bigger than 8 1/2"x11" I can do it at home on my Epson printer.

Nobody's found the Hancock's spar dimensions. After a good deal of thought I decided to use those of the Raleigh, another 32-gun frigate that was under construction at the same time. The Raleigh was built at Portsmouth, New Hampshire; the Hancock at Newburyport, Massachusetts. James Lees's fine book, The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War, was an enormous help in this model. It seems pretty safe to assume that American shipwrights and riggers in 1775-6 generally followed British practice.

My late father (a retired architecture professor, who had extensive training in sculpture and aesthetics) helped me out in designing the mounting pedestals. Getting the height, diameter, and placement of those things is pretty important to the overall appearance of the model. I think we got it about right this time.

The model normally lives in a plexiglass case with a walnut base. (That's the big reason why it's lasted thirty years.) For the pictures I ran a Savage paper photo backdrop behind and under it.

The figurehead of the real ship was slightly larger than life-size. By pure coincidence it turned out that an HO figure from the extensive Preiser line who had his arms folded across his chest was just the right size. He had to get a new hat, coat, and legs. A letter from Commodore Sir George Collier describes the color scheme of the figurehead in remarkable detail.

Making the stern was quite a little project. It's built up from styrene sheet, styrene strip, Milliput epoxy putty (wonderful stuff), and clear plastic (though there's nothing inside except a little sign reading "Sorry, no interior detail.") The letters for the ship's name are from a set of styrene alphabets that used to be available from Slater's, of England. The serifs are doctored with Milliput. The muntons in the windows are white decal stripes; the "Don't Tread On Me" lettering is from an N-scale decal sheet from Microscale.

In real life the transom is about 3" wide. Blowing up this image on a nice new Mac screen is a humbling experience. I can see now that the top of the left hand window is a little crooked. My bad.

The crew figures came from several plastic kits that happened to be just about on the right scale: the Revell Bounty, Santa Maria, and harbor tug Long Beach (!) and the Airfix Endeavour. They got pretty extensively modified with plastic sheet and Milliput. (The green-coated Continental Marine on the forecastle deck a couple of shots back started life as a helmeted Spanish soldier on board the Santa Maria.) The only sign of the model's age is the green patina on that guy's telescope. The scope is brass; I varnished it, scraped it, and cussed at it, but it kept turning green. Sometime after I took these photos I finally gave up on it, decided it's a leather-wrapped telescope, and painted it black.

The wheel rims and hub were turned from brass, and drilled with the Unimat's indexing head. The spokes are plastic rod, built up to profile with a mix of PollyS paint and white glue.

The two binnacles in front of the wheel have compasses inside them, made from a set of 1/72 aircraft instruments. Actually only one binnacle has a compass. I succumbed to irresistable temptation and put an altimeter in the other one.

The boats were made with a technique I learned from an old book by Ewart Freeston called Modeling Open Boats. I started by cutting a piece to form the keel, stem, and sternpost from a piece of holly. Then I cut two blocks (also holly) to form the two sides of the hull - with the growth rings of the wood radiating out from the centerline of the hull at the top. (That's important.) Then it was a matter of carving the exterior to shape, and hollowing it out. The trick there is to hold the workpiece over a light bulb as you carve. When light starts to show through the wood - STOP.

Here's a trick for making oars on this scale (and smaller). Heat up a straight piece of brass wire over a candle, let it cool, and mash one end of it in a vise. The mashed part becomes the blade. Cut and file to shape.

The hammocks are tissue paper, treated with my favorite mixture of acrylic paint and white glue. I don't remember how long it took to make all of them. The netting is nylon material from a fabric store. The trick is to find netting with square mesh. Most of it is hexagonal or octagonal. With 20/20 hindsight I realize that the mesh I used is actually too fine for the scale. Noted for next time.

The deck gratings are britannia castings from Bluejacket. Unfortunately the company doesn't make them any more. The berth deck only runs under the hatches, where it can be seen.

The gun barrels were turned from brass on my dear old Unimat lathe. The trucks (wheels) for the carriages, and the handles on the quoins, were turned from boxwood. (Great stuff if you can find it.) The other parts of the carriages are made from styrene sheet.

The spars are turned from degama, an extremely dense hardwood that can be turned down to a really fine diameter and almost refuses to bend. (It does, however, break. I found that out the hard way - more than once.)

Most of the rigging is silk thread, spun up into several dozen diameters on my primitive "rope-making machine." (I made it from a Lego set, and it worked just fine.) The big exceptions are the ratlines, which were made from nickel-chromium wire. (A friend picked up a spool with several miles on it at a military surplus store.) That turned out to be great stuff for the purpose: it can be tied in a clove hitch, and teased so it sags between the shrouds. The footropes are brass wire. The blocks and deadeyes are britannia metal castings from Bluejacket. I lost count of how many I had to buy, but the expense was spread over several years. I got six years (with several long gaps) of modeling out of less money than a 1/350 Trumpeter battleship costs today. (That doesn't count the plexiglass for the case, which, as I remember, was the biggest single expense.)

According to the tables in David Steel's Elements of Rigging and Seamanship, a 32-gun frigate like this was issued with about fourteen miles of rope. I believe it.

Looking at this thing now I have to wonder whether my 62-year-old fingers and eyeballs would be up to doing it again. I doubt it.

The sails are made from lens tissue, treated with a mixture of PollyS paint (as it was called in those days) and white glue. I've described the technique elsewhere in the Forum. Why I thought all those sailors should look so anemic I have no idea.

The skinny little bundle of spar and canvas lashed inside the topmast shroud is the fore topgallant royal yard and sail. During this period the topgallant royal was a temporary, fine-weather sail set above the topgallant, with minimal rigging; when it was furled the yard and sail were sent down and stowed like this. By a decade or so later the topgallant royal had morphed into the true royal, whose yard that was more-or-less permanently secured to the mast.

The photos, if anybody's interested, were taken with my dear old Pentax 35mm film camera, before I went digital. (It still works perfectly - though most of the time I use my digital Pentax K-10.) The background, as mentioned earlier, is a Savage paper one (about $25 from Adorama or B and H Photo), and the light came from three daylight-balanced blue photo bulbs mounted in "clip light" reflector fixtures from Lowe's, with cheesecloth diffusers. (I've got a better lighting setup now, with umbrellas.) The film is Fuji Reala. I had the negatives made into a digital disc, so I could Photoshop them.

Thanks for looking. Someday soon I'll try posting some pictures of other models. Getting the pix from Photoshop Elements on a Mac to Photobucket to the Forum is a little complicated, but I think I'm getting the hang of it.